Have you ever stood, a nobody among the pews, at the back of a cathedral during high mass? I suppose it’s unlikely — church attendance is not much of a thing anymore, Christianity being on the outs.

Still, there’s something awe-inspiring about it: the crush of brass in the crescendo on “Jesus Christ is Risen Today,” or the gently stirring organ voluntaries of early advent, weighted down with reflective minor chords. The bigness of it makes you feel insignificant — yet, somehow, part of a greater, universal project that nobody has ever managed to satisfactorily explain.

#

Decades a Catholic, I spent much of my early life feeling bound to the church — and to God — by obligation. Then, in an early-‘20s theological about-face, my spiritual life latched to Martin Luther’s notion of Christian freedom and spiritual individualism. Purpose was mine to uncover and live; obligations be damned. I reveled in hymns that celebrated this freedom, relishing “high mass” music in my own, reflective, emotional way.

More so, I dove headlong into everything church: what I jokingly called “volunteerism for Christ.” Only it was less about Christ, I’ve come to realize, and more about the community. I deeply admired the people with whom I worshipped — not because of their saintly accomplishments, but because they were fueled by a passion for the greater good. Ups and downs never stalled their work, life lived in the purpose of bettering the world around them.

As too often happens, politics infected the community. Control-fevered (and money-powered) church-goers took the reins, rewrote our mission, ignored the voices of those who dissented. Over time, the community dwindled, along with the inspiration that fired me. In a matter of months, church became an obligation again. So, I left.

But other obligations rushed in to fill the void. Now, I’m bound to the challenging must-dos of adulthood in a weird and hard-to-parse generation. Life is lived day by day — but not in a “present in the moment” reveling. No, it’s more of a survivalist tack, taking me from work demands to panicked financial solutioning and banal errand-running. This is not new to me or my generation, I realize; it feels very much as Maya Angelou described: “… carrying the accumulation of years in our bodies, and on our faces…”

In this draining survivalism, I have lost sight of purpose or meaning. The “greater good” is an abstraction, but even if it were concrete, I would lack the energy to invest in it.

That’s why, on a lark, I stumbled back to church on a recent Sunday. “Maybe God will have me back,” I mused. “Maybe we can start this thing again.”

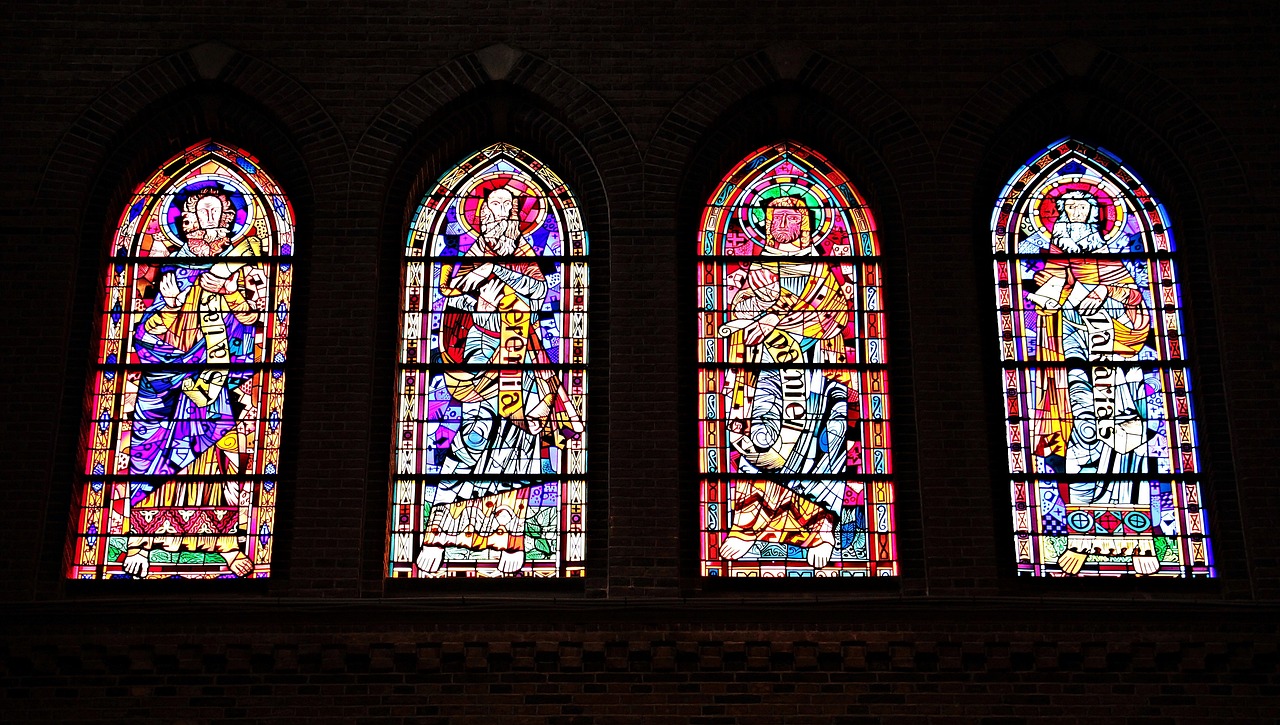

But my entrance was marred by guilt. I avoided eye contact with the bishop on the front steps, sheepishly scuffing along the side of the church, finding an out-of-sight seat at the back. Then I looked up: In sweeping stained glass, Mary Magdalene and the tattered apostles glared down. I sighed deeply, feeling guilty for abandoning something — for abandoning them.

How could I come back now? A misguided Peter, a cowardly, doubting Thomas. I was tempted to leave.

As I weighed the pros and cons of staying, out of sight, until at least the sermon, the organ pipes began to bellow. My eyes shifted to the glowing stained glass in the apse behind the altar: Jesus, whiter than ever, floated among clouds held in place by cherubic angels and misfit disciples. I locked eyes with our whitewashed savior as the unrelenting , guttural chorus of “O Filii et Filae” reverberated in every ceiling swell and shadowed alcove.

There is a verse in this hymn — probably my favorite of all time — that sounded louder that particular Sunday: “When Thomas saw that wounded side, the truth no longer he denied; ‘Thou art my Lord and God!’ he cried. Alleluia! Alleluia!”

A soaring hymn celebrating the doubt-turned-faith of another one of us, nobodies on the outs. Hardly a thing to trumpet, yet there it was. I looked back up at Peter — his face carrying the accumulation of doubt, denial, suffering, and not a small amount of guilt. “We’re not so different, you and I,” I quipped, just as the hymn sounded its final, epic chord.

This is why — despite the politicking that contaminates the church, and all the doubt that contaminates me — I still come back. The music reminds me there is bigger work to be done, and among the messy contingent of faithful and doubting, I can still be a part of it.