No doubt you heard the news: Salman Rushdie, sometimes-incendiary literary icon, was attacked during a public event at the Chautauqua Institution in August. He was stabbed in the neck and abdomen. Surgery helped with recovery, but he lost sight in one eye. The attacker’s motive? Still unclear.

I remember where I was when I heard the news: In bed, flipping mindlessly between Instagram reels and Apple News. It had been a long day (aren’t they all anymore?); all I really wanted was to numbly, passively digest ridiculous content to distract me from what was just around the corner — another day of anxious work meetings, impossible deadlines, and seething reminders that my life seemed to be stalling out.

You couldn’t say the same of Rushdie. Ever. Decades before the Chautauqua event, he published his seminal work: “The Satanic Verses.” It was met with condemnation from the Ayatollah of Iran in 1989, resulting in a fatwa (or religious edict) targeted specifically at Rushdie. Kill the author of “The Satanic Verses,” he ordered. From then on, life was a nightmare.

For decades, Rushdie lived in a state of fear. Attacks at any point were possible — in fact, he spent nine years under police protection. Friends and heads of state urged him to pull the title and back away from its message. Detractors emerged from every corner, and while it proved inspirational to some writers, what dominated the news was the broad vilification of Rushdie owing to “aspersions cast on the Prophet Muhammad.”

They got it wrong, but nevermind. “The Satanic Verses” was about migration — losing one’s roots, one’s identity. It wasn’t meant to be at all religious. But nevermind.

Fast-forward to 2022. Fear had ebbed. Rushdie began going out in public again. In fact, he became something of a fixture in the New York City nightlife scene, prompting onlookers to ask if they should be scared. Could someone come for him, right there, in a restaurant in the Bronx?

Rushdie was unfazed. “I have to live my life,” he said.

#

A week ago, I tucked into bed to find another Rushdie article probing me. This one was all about his defiance in the wake of the attack: a revisitation of the unorthodox life of a man who has stared down religious hatred and continued to create.

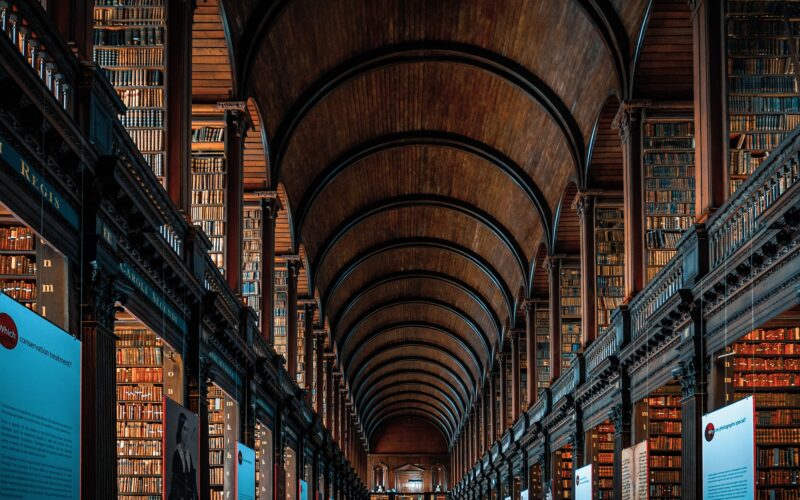

It left me number than usual. I often seek out life histories of authors I enjoy, simply to find the nuggets of inspiration that pushed them to create. It’s a tightrope walk: a constant reminder that I have not achieved any measure of literary greatness while humbly sucking the marrow from giants so that I, too, can write my verses.

Rushdie is out-of-bounds. A fatwa? Heads of state decrying blasphemous characters? It’s just not anything I can relate to. And yet, his unique creative path is what intrigues me: a man undeterred by the wildest of polemics and unspeakable aggressions that cross nations. He’s continued writing since “The Satanic Verses” because, well, he’s a writer. Inspired by magic, the tenuous boundaries of realism, and the possibilities of scrap-cloth fiction.

If ever there were a reason for a career change, Rushie has it. A call for his head from Iran’s supreme leader? Most of us wouldn’t blink before finding a hole to hide in. Or, in my case, a cavernous bed where numbness would not only be understandable — it would be encouraged.

But no. Call Rushdie what you will — a firebrand, a provocateur, an unnecessary instigator. In the wake of the recent attack, friends wondered often and out loud about the merits of taking imagination to Rushdie’s dangerous ends — ends that knock into the boundaries of free speech and religious propriety. In the face of all of this, he keeps on writing. Because he’s a writer.

Wait. Is that quite right? Even I, at this point in the narrative, begin to furrow my brow. Life at gunpoint, a fatwa and denunciations from high and low, a life on the edge of an abyss, and writing still the vocation?

It seemed too much. So I asked him out-loud, rolling around in my sheets and puzzled by this writing mania: “Why push so hard? Is there something you believe in so strongly it must come out, whatever the consequences?”

The question hung in the air, unanswered. Moments later, I uncovered a banal quote at the end of The New Yorker article chronicling Rushdie’s journey: “I’ve always thought that my books are more interesting than my life,” he said.

And it clicked, in some distant corner of my mind. Rushdie doesn’t write, hasn’t written because he’s a writer. No, that’s too basic. Too one-dimensional. Too… essential.

His writing is his living.

I realized in that moment — at 10:02pm on an otherwise unremarkable Wednesday —that writing as living is exactly what I have not been doing. I write to please, to create, to check boxes. Not to live.

What would it look like if I tossed out the “musts” and stoked the fires of imagination a bit more? What does my soul look like on fire, kindled by words? How can I live more fully, completely, in my verses, my stories, my backwards characters?

How can my writing deliver a life more alive?

I’m not suggesting I get flippant, dismissive. I’m suggesting something subtler — a reconsideration of rules gone stale, putting normality and routine squarely in the dock. Playing freely with “what if’s…” and odd cultural dissections that stir the very things that stir my soul: Belief. Human rights. Common decency. Love. Creation.

It’s time to take them off the shelf, one by one, put pen to paper … and get to living.