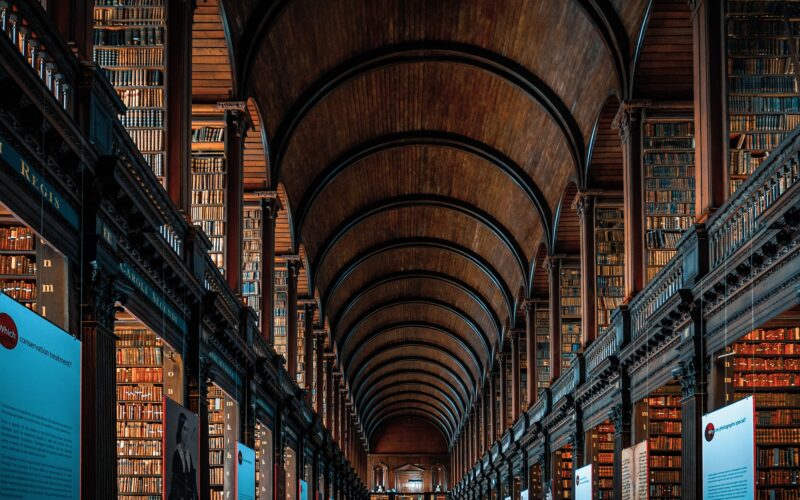

Johann Hari sat in the middle of the surf, his bare feet consumed by the ocean. To be more specific, he sat in a flimsy plastic folding chair, on a rocky beach, beneath a sea of sunken clouds, on a Tuesday reading “War and Peace.”

This image was offered up in the New York Times best-selling book, “Stolen Focus.” While the book’s premise has nothing specifically to do with writing, Hari’s deceptively idyllic ocean scene seems a perfect metaphor for the writer’s modern-day crisis. So I’m going to borrow it.

Create a chair (something written) that must stand the test of seas and time, supporting society through life’s inevitable ups and down. Something that will allow us to focus on what we care about — our own”War and Peace,” the litany of self-appointed priorities and passions.

But for god’s sake, do it quickly — and do it cheaply.

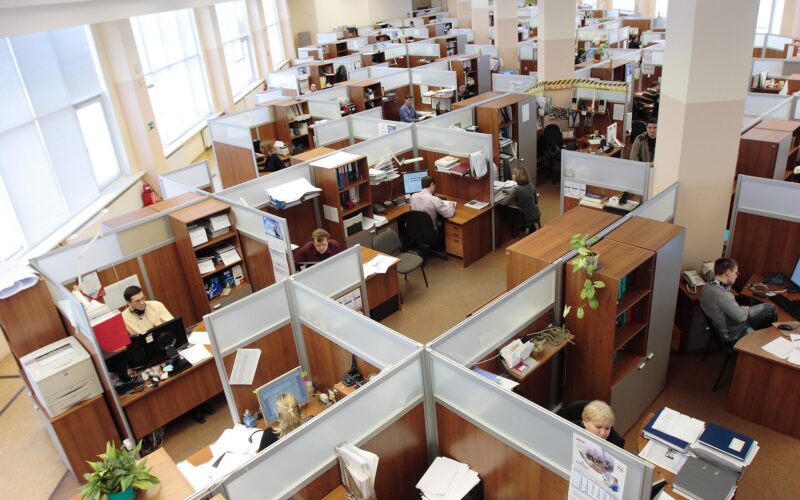

As a professional writer, I’m often asked to produce content at lightning speed. There is little time to sit and think, theorize, or plan. I simply have to get “it” out the door. And with the digitalization of everything under the sun, even the artistic renderings of a writer are hurriedly linked to metrics: How many views did it get it? How many clicks? How soon can we call it a failure, a success?

I want to be clear about something: I think often about the adage, “Only bad craftsmen blame their tools.” If I write something genuinely terrible, I cop to its atrociousness. Still, I can’t dismiss society’s tightening clamp on creativity that makes writing less of a vocation and more of a factory function.

Put another way, our rush to produce content in a digital world means we have two masters: Quality and speed. The average marketer, business person, or Jane on the street would ask us to serve both simultaneously. And why not? Isn’t that simply a skill you develop?

Yes. And no.

On the one hand, creating something can be done quickly — and it can be called, on a very fundamental level, “good.” After all, didn’t Bob Ross paint heartwarming vistas in 30-minute TV episodes?

That “good,” however, is a depreciation of what “good” ought to be. For most non-writers, “good” writing hits a basic mark, largely quantifiable: Views, clicks, likes, shares, etc. It doesn’t begin to consider the likelihood of impact beyond basic metrics, an impact that is much harder to gauge. Did a piece of writing change someone’s mind? Did it begin a debate to address roiling concerns? Did it make someone, for a brief moment, reconsider dire or dangerous ambitions?

No sane strategist would deny the value of these things, but the pace of society — and inability to measure their effect in a world almost entirely measurable — means a different approach is necessary. If we must work within the bounds of clicks and views and likes, let’s twist them to affect the change we seek. Simplify and volumize the message so that it resonates with as many people as possible.

Don’t waste time and resources creating a chair that stands its ground, however aggressive the tide. Create a million plastic chairs — if one breaks, we’ll just replace it.

Here’s the rub: Every time the chair breaks (and it breaks fairly often), we lose focus waiting for a new one to take its place. We’re getting better at that transition, to be sure, but it still pulls from immersion in our own “War and Peace.” Not infrequently, we have to reread paragraphs and chapters because we’ve lost our focus. And in that loss of focus, we are unable to process the complex meaning and value of what we so desperately want to spend our concentration on: family, friends, community, passions.

#

I have a confession: I’ve never read “War and Peace.” It’s daunting. Who has the time?

Except, I do. I choose not to read it because I’m afraid my plastic chair will crumble in the aggressive surf beneath a sunken sky on a Tuesday. I would have to start and restart and reconsider. I wouldn’t make any progress. Better to just swipe and click and like and be done.

Right?